At a time when there is much thought about «what lies ahead,» our writer wonders what a once-popular genre can teach us about the confrontation between life and fiction. And whether it wouldn’t be decidedly better to embrace both.

Definition is the first problem that arises when talking about sitcoms. What is a sitcom ? What are the limits of the term? If we say that “ Friends ” is the sitcom par excellence, it is natural to ask whether it does not represent a real genre in itself. The etymology of the word can help explain its meaning. Sitcom is the contracted form of “ situation comedy .” Therefore, a comic system linked to a situation. The word “situation” is one of those difficult to define: it can be defined as the presence of people and objects within an environment. Specifically, sitcom could mean the comic presence of objects and people within a specific environment. This same term (in English “location”) raises a series of questions: can we define it as a specific set, which never changes – as happened in the first original situation comedies of the 50s and 60s? Or could it be an entire city, for example, as in the more modern series “ Beverly Hills 90210 ”, which actually featured a mix of genres? What if the setting is central, but the action of the program takes place in many other places – as can be seen in the hit show “Call My Agent!”, airing on Netflix France?

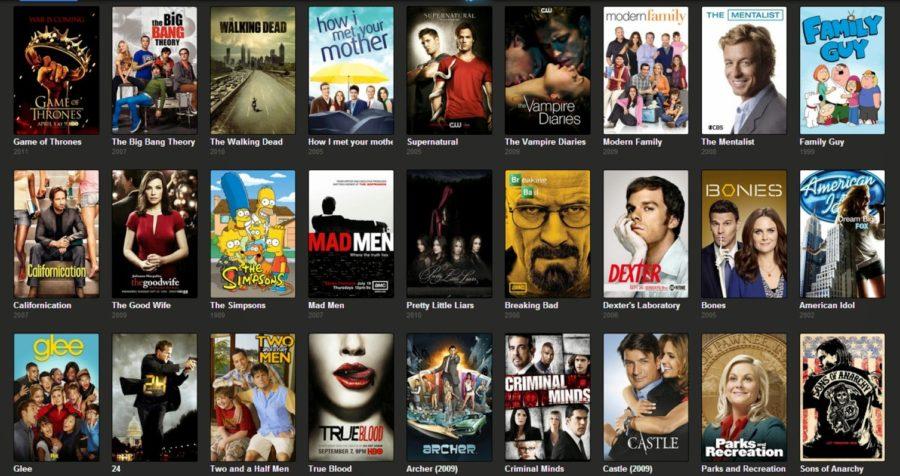

Another difficulty in identifying the meaning of situation comedy is linked to the origin of this genre: sitcoms are considered a true American cultural giant . In the 80s, everyone in the world watched American comedy series. Matthew Perry and Jennifer Aniston were our friends. Those of us who belong to the pre-generation Z knew them as their contemporaries, and now the new generations watch them on streaming. One could go so far as to argue that knowledge of sitcoms separates those who now belong to a bygone world — that of American culture exported abroad, in which a few series dominated the globe — from the inhabitants of the new world, who perceive Millennials as already too old, and who do not need to live the experience of sitcoms as a window on life, because for them life itself is a sitcom.

What made sitcoms special was the presence of familiar characters in an environment that became as familiar to us as the environment we live in. We were as accustomed to the apartments on “ Friends ” as we were to our own homes, whether we lived in New York, Paris, Tokyo, Delhi, Lagos, or Los Angeles. At a time when we no longer had a “home base”—thanks to world travel, in the case of the more fortunate of us, or to the discovery of new worlds on the Internet, a possibility, this, accessible to all— sitcoms gave us a reassuring sense of “home .” These people had a home. They had a life. They lived, they loved, they were friends. The Americanness of this utopia—the utopia of social happiness —went beyond the globalization of culture, and became localization: Brazil, India, France, Italy, Spain, and Latin America all began to create their own versions of these fictional friends. We wanted to be part of the utopia of having a home and friends, of loving, living, and staying forever young. These friends were the family we dreamed of having . Family is given to us, and we give it to others. It defines us, and we define it. It is the center of our lives. Sitcoms offered us the opportunity to create a family of our own choosing in fiction.

Even if you were young and had friends and happy family, the life that was offered by sitcoms was a better version of the one you had. It was possible that there were princes in Bel-Air , and although the character in the series was loosely based on Will Smith’s own experiences, no one really had a life like “The Prince.” The compression, serialization, and transformation of everyday life made his story a dream for all of us.

In this regard, sitcoms gave rise to a certain kind of reality show. The Kardashian sisters were indeed the stars of a sitcom, but the show was the supposed chronicle of their real lives. Allowing one’s life to be filmed for others was profoundly Duchampian: it turned life into a pre-packaged product. Of course, the choice of which life to tell was not accidental, just as it was not truly pre-packaged. Instead, it was a deliberate choice to present a kind of concept to the public.

Sitcom characters – as in reality TV – have no psychology . They have passions, yes, and are overwhelmed by strong feelings, but then life goes on. In the sitcom version of existence, there is no room for resentment . Over the course of the various seasons, both hate and love pass. Sometimes they return. But these characters do not act on the basis of their emotional baggage, they live in a permanent state of reaction to the single moment.

I remember when, at a dinner at Azzedine Alaïa’s house, of whom I was a close friend and collaborator, I explained to Kim Kardashian the reasons why Pierre Guyotat had written “ Coma .” He was talking about trying to exonerate himself, about being aware of being on a stage or in a field. And Kardashian agreed with me: that was exactly what she did and how she lived her life. Transforming herself into a sort of stage on which to make things happen, thus refusing the separation between the private and public dimensions. Life was one, and it flowed in a continuous flow. In the case of both Kardashian and Guyotat – with due differences, of course – these were existential, heroic choices. Allowing themselves to be seen as creators of image and textuality, being simultaneously themselves and others , identifiable and at the same time empty figures with whom others can identify. In “Ion,” Plato talks about “enthusiasm,” or being possessed by a divinity that gives poetry to our voice. To be possessed, one must be empty. It is not possible to experience complex, multifaceted, conflicting feelings. On the contrary, they pass through us, and we are the vessel that carries them in one direction or another.

This way of thinking beyond the psychological dimension spread to culture thanks to sitcoms: since they were not only defined by their protagonists, but by the situation, they were not about the characters. It was the environments that were exploited, moved, changed. There was nothing personal, and for this reason the series took on a relational value. Sitcoms were entirely dedicated to relationships: between families, friends, friends who became like families. For many of us, the people on our TV screens were also our friends, our family .

There’s a classic, traditional definition of a sitcom, tied to the idea of a set that never changes. Another instead associates that same set with another era – are we not yet past the age of the sitcom? Or we could extend the meaning to the present, and that’s what I would do. Because in that case they could become a fascinating metaphor for what we have become: we call people our predecessors strangers as friends, we don’t distinguish between reality and fiction and we have a romantic, at times surreal, idea of our lives. Maybe sitcoms were once a form of escape from everyday life, they showed us the life we wanted to have and that we thought we were entitled to. Are you a Carrie ? Are you a Miranda or a Samantha ? A common question in the ’ 90s.

This is certainly linked to a desire for escape. But above all, situation comedies allowed us to bring magic into our lives. They gave us friends who didn’t want to be our friends. One of their essential characteristics was the existence of a sort of company, a group of actors, who we dreamed were our friends. They had to be our friends to belong to us. Sitcoms made us believe that life could be a novel, an epic adventure, a series – and this concept later extended to reality TV and social media.

Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, every social media is a sort of sitcom in which each of us is participating, more or less consciously. As William Shakespeare would say: » All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women are players upon it .» But what would happen if we collectively decided that we didn’t need escape? And that we didn’t need fictional friends? Our very lives could become a fiction, and we the heroes of our stories. We love each other, we don’t love each other anymore, we are friends, we aren’t, we talk to each other, we don’t talk to each other. We share our lives.